This flu crisis was unparalleled in history. The future of horse racing was so much in doubt that the Daily Racing Form wrote, “The wheels of the organization are practically at a standstill for the time being.â€

Horse racing was in trouble. Tracks in Maryland closed their doors. The Latonia Jockey Club in Kentucky had to delay its meeting because state officials banned public gatherings. Public health officials followed suit, banning large public gatherings on a state-by-state basis. The ban threatened hundreds of races across the country, including the Kentucky Derby.

This all happened in 1918 and 1919, during a post-World War I influenza pandemic. Commonly called the Spanish Flu (even though it originated in Kansas), this virus killed between 20 and 50 million people worldwide, including 675,000 in the United States.

Horse racing is going through similar turmoil right now. But it’s nothing the sport hasn’t seen — and survived — before. Whether it was a flu epidemic 100 years ago, a track being converted into a Japanese internment camp during World War II, or the 1945 Kentucky Derby coming as close as any to being canceled (but wasn’t), our current predicament finds itself in familiar historic territory.

Horse Racing’s History of Adaptation

While COVID-19 is currently bringing the sporting and social worlds to a standstill, the history of horse racing is replete with examples of adaptation to both human and equine epidemics and pandemics.

Riding shotgun with the influenza pandemic, the equine strain of the disease cut a swath through the stalls at Belmont Park in the winter and spring of 1919, killing more than 100 thoroughbreds. That was just one incident in a series of outbreaks that would infest the sport well into the 1930s.

The COVID-19 pandemic has already left an indelible mark on the sport’s history. It pushed the Kentucky Derby out of the first Saturday in May for the first time in 75 years and has closed racetracks all over the world.

The 2020 virus threat also led to the rare cancelation of the Grand National, which was supposed to run this weekend.

World War II did stop the Grand National from 1941 to 1945, but it didn’t stop horse racing in the UK.

During those years, Great Britain turned many racetracks into Royal Air Force bases, including Newmarket and Bath. The Newmarket July Course played host to the Derby in place of Epsom, however. And while Ascot suspended its Royal Ascot races, the track ran smaller meets while using part of the facility as a German POW camp.

But the Kentucky Derby kept on running during World War II. It came closest to skipping a year in 1945, in what would have been the first time since 1875. Had the war not ended when it did, it may have been a different story.

Santa Anita Notorious as World War II Footnote

During the early part of World War II, racing continued at most tracks in the United States – with one notorious exception. In February 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, mandating the internment of Japanese Americans.

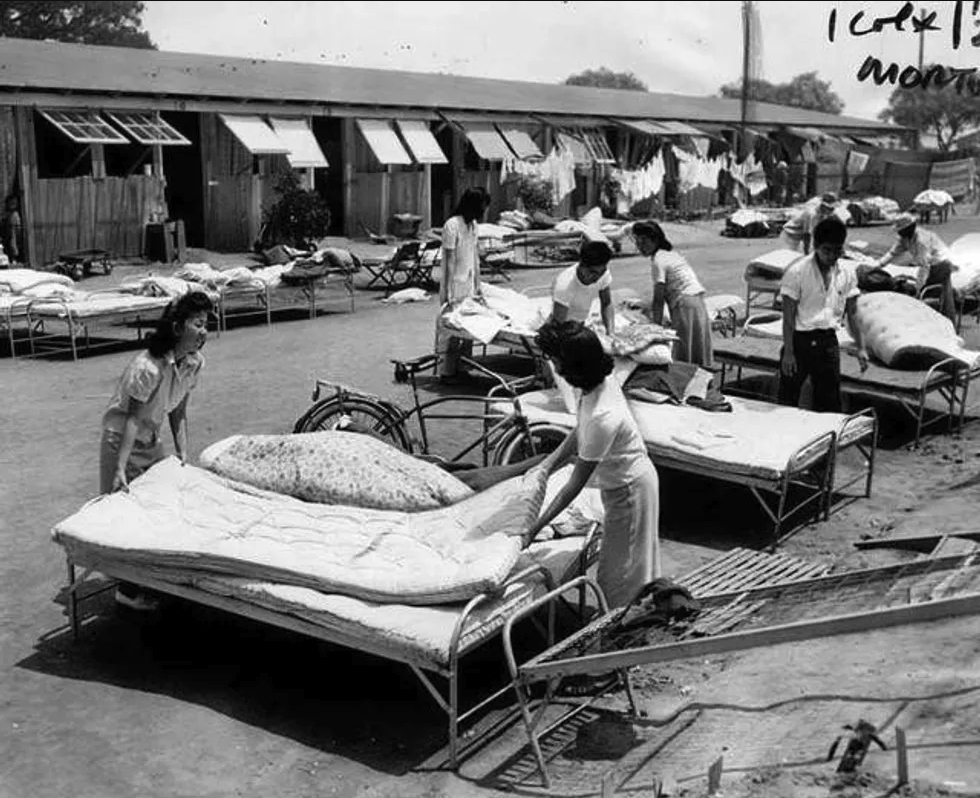

While the camps were under construction, Santa Anita Park in California became the Santa Anita Assembly Center – housing Japanese Americans awaiting transfer to more permanent detention centers. It was the largest such facility in the country.

Between February and November 1942, nearly 19,000 Japanese Americans passed through a heavily guarded gate to the barbed-wire-encased track. They lived in the horse stalls and were forbidden from having anything written in Japanese. But they still built a community with a strong internal economy, businesses, culture, and even a local newspaper. The $2 window became the check-out for the camp’s library.

(California officially apologized for the state’s role in allowing Japanese internment camps just this past February.)

As the war progressed, the Kentucky Derby kept running. More than 70,000 fans attended in 1942 and 61,700 in 1943.

In January 1945, however, the federal government ordered all dog and horse tracks to close until the war was over. The purpose was to conserve resources such as trains, electricity, and fuel for the war effort. War Mobilization Director James Byrnes estimated the ban freed up 19,000 miles of telegraph wires and telephone facilities – previously used to transfer race results across the country.

But by April 1945, Byrnes, a Kentuckian, put out the word to track owners and horsemen that they should get ready for racing to resume shortly. On May 8, Nazi Germany surrendered. The threat to the 1945 Kentucky Derby had passed, and the race would be held a month later, on June 9.

Legendary Jock Wins Delayed Kentucky Derby

In the first Run for the Roses not run in May, Hall of Fame jockey Eddie Arcaro guided Hoop Jr. to a six-length victory over favored Pot O’ Luck in front of 75,000 fans. They wagered a record $2,380,796 that day, with also a record $776,408 bet on the Derby itself.

The other two legs of the Triple Crown also adjusted accordingly in 1945. The Preakness Stakes ran June 16, with Polynesian beating Arcaro and Hoop Jr. A week later, the Belmont Stakes ran, and Arcaro got back in the winner’s circle, riding Pavot. This horse didn’t run in the Derby and finished fifth in the Preakness, but carried Arcaro to the third of his co-record six Belmont Stakes titles.

Today, there is again uncertainty about racing’s future, especially since the sport reels under a diminishing stock of horses, declining fields, a burgeoning drug scandal, and an erosion of popularity since its postwar heyday. But through pandemics, wars, and depressions, the sport of kings has found its way back to the starting gate each time.

Kiplingcotes: Keeping a 500-Year Tradition Alive

The reverberations from this latest outbreak extend to one of the world’s oldest races. The Kiplingcotes Derby celebrated its 500th running last year in front of a crowd of 1,500. But this year, no one was present.

Since 1519, the Kiplingcotes Derby has run in East Yorkshire on the third Thursday in March. This year marked only the fourth cancellation of this race in 501 years.

However, according to its Renaissance charter, the race must be run every year, or never run again. So in 2020, with half a millennium of history in the balance, jockeys Stephen Crawford and four-time winner John Thirsk — along with a race secretary to make matters official — walked the four-mile course. By doing so with their mounts, Harry and Ferkin, they kept the race alive.

Keeping the organization of horse racing — or a 501-year-old race, for that matter — alive during wars and pandemics isn’t much different than keeping victory alive for a horse down the stretch. It just requires a little adaptation to the circumstances.

It is a shame Equine Influenza 2007 -2008 was not mentioned in this article.

The extreme measures to keep Racehorses alive and racing afloat during this time is unparalleled.